The way historians organise and carry out their research has changed over the past two decades. We no longer (only) spend time in archives, but consult archival material more and more via online databases and repositories from our office or the comfort of our living room. The repositories are managed by libraries, universities, research institutions or independent companies, and store millions of scanned material such as letters, objects, pictures, periodicals and books. I want to address some key issues, possible solutions and good practices within digital historical research, based on my own experiences working with digitised periodicals and books.

The first step in historical research after selecting and localising source material in archives or online repositories is consulting sources. Source consultation is no longer limited to reading through boxes of archival material in the reading room and taking notes. With recent changes in digitisation, the historian’s research trajectory often involves downloading or scanning source material. Nowadays you push a button on your computer or on a scanner and in no time you can acquire (almost) all the material that you need. This sounds easy, but it is not as straightforward as it seems. The quality of the scans, metadata, OCR, …. — popular terms in digital history journals and lectures — all have an impact on how usable and trustworthy our digital sources are. In some ways the use of digitised sources and the state they are in, can make or break our research findings.

Downloading or scanning?

Digitisation of historical sources by libraries, universities and archival institutions has improved accessibility to researchers and the public alike. However, this trend also impacts the work process, especially for the historian. The interpretation of sources and their content has now also become dependent on the quality of the digitisation. Three standard options have become available to historians who want to use digitised sources: 1) download sources scanned by third party institutions 2) get into a project partnership with an archive or library to digitize a specific collection for a research project or 3) scanning the collection of sources yourself with the necessary equipment.

-

The download button

Professional scans are often made available by HathiTrust, BnF Gallica, Google Books or Archive.org amongst others, often in cooperation with each other and with university libraries and archives. In this case the researcher depends on one or several third parties. On a positive note, researchers don’t have to waste time scanning material when third party suppliers provide the content in multiple formats: pdfs, txt, epub, html. However, the precision and quality of the scans can vary greatly. Sources can be in black and white (bi-tonal), grayscale or colour. Research has shown that the resolution of the files as well as its formats (pdf, jpg, png) impacts the readability for the scholar, as well as the quality of the Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and the outlook of the text files that are created. [1] Furthermore, pages can be scanned individually or two pages at a time. Especially for OCR processing the latter is inconvenient. Sometimes pages are missing or badly scanned, not providing researchers with the full book or corpus. Many of these advantages and disadvantages should also be taken into account when making your own scans (see images below).

Figure 1. Scan errors. From left to right: no text is recognisable on the page; page is turned to slow or too quickly, finger imprints on the page; poorly scanned page.

[masterslider id=”3″]

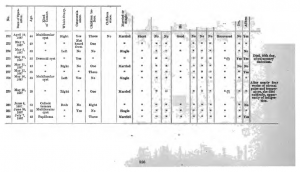

Figure 2. From left to right: scans in varying degrees of colour tones, as well as black and white and greyscale scans. Black and white scans are most optimal for the OCR rate, but aspects such as colour are lost to the historian in his/her analysis of the source.

Figure 3. The resolution of the images is also important for the readability of the source for humans as well as computer software.

-

Scanning on demand: nice but expensive

Professional scans made by archives and libraries are produced with very different equipment depending on the material of a source, as well as the budget of the institution. The equipment can range from contraptions of high definition cameras such as the BookDrive from Atiz— often used for books with paintings or pictures —, overhead book scanners (more below) or semi-automatic book scanners such as the Treventus Scan Robot. Many archives and libraries offer scanning on demand, but often only for large scale projects with sufficient budgets. Scanning entire collections can quickly become costly and run up to 1000 of euros for a fraction of a collection. Furthermore, the time investment from the researcher(s) as well as the archive/library cannot exceed the duration of the project. For small scale projects without a large team, scanning on demand is often not an option.

-

Self-scanning: the devil is in the details

Apart from on demand scanning, researchers often make their own scans. The easiest method is photographing with a camera or smartphone while working in the archive. Although convenient, quickly taken photographs at strange angles are not ideal to analyse and process. The advanced option is overhead scanning machines, sometimes available to the public (i.e. researchers) in libraries and archives in various formats and sizes.

The first type of scanner I used is an overhead scanner without a V-shaped book cradle, but with a horizontal metallic plate that can be pressed down to accommodate smaller and wider book spines. Problems occur when a double page is scanned with the left and right side not equally flat. Both sides have to be readable and the text should not disappear into the margins. Scanning each double page twice reduces the problem, but this is time consuming. Furthermore, scanning two pages at a time means post-processing with sometimes expensive and inadequate software to improve the conversion to text files. A massively used pdf reader such as Adobe Acrobat pro for example does not have a function to automatically split pdfs into single left and right pages. Another challenge is avoiding or removing scanned fingers from pressing the book down on the scanning installation. Although this does not impact the text in the scans, it is not aesthetically appealing.

Figure 4. Left: flat, single page scan. Right: double page scan. Notice that the text is bent at the inner sides of the scan, which is less convenient for readability and the OCR rate.

The second scanner I used was the BookEye 4 scanner, which has more functionality (colour, black and white, greyscale scanning) as well as a thumb removal mechanism. Unfortunately the institution charged extra for automatically splitting double pages. The most important difference however, is the different shape of the book/journal cradle. Instead of a horizontal plate, the BookEye4 scanner is V-shaped. Pages can usually be scanned similarly on both the left and right side, making OCR rates more accurate.

[masterslider id =2]

Source: Fujitsu ScanSnap SV600 Overhead Scanner, Bookeye 4, Treventus, Atiz Bookdrive Pro.

Next stop: OCR quality

As illustrated by previous examples the quality of a scan impacts how the material can be processed. The quality is closely correlated with the format (pdf or jpg/png/tiff images) and the year in which the scan was made, due to improvements in equipment. Digitised sources come in different downloadable formats, but most often we use PDFs. When a pdf is not OCRed yet and text needs to be extracted, images are better because the structure of the original source stays intact (see image).[2]

[masterslider id=”4″]

Figure 5. From left to right: original page, text file acquired from pdf, text file acquired from image.

Besides the hardware and its functionalities, OCR software also influences quality. OCR can be done via the terminal using packages such as Tesseract or pdftotext to extract text files from a pdf. Other software with a graphical user interface such as Abbyy FineReader is used more often. As technology changes rapidly, the quality of a scan made in 2010 with Abbyy FineReader version 8.0 (version from circa 2005) will not be the same as a scan made in 2010, with Abbyy FineReader’s latest version (version 14.0), or a scan made and OCRed in 2019. Rescanning the collection would be inconvenient and expensive for libraries and archives, although it could be profitable for very old scans. However, updating their digitised collections (i.e. outfitting them with the latest OCR software) could already improve the usability of these sources for researchers.

Solutions?

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for issues such as blurred or missing pages, bad scan quality, etc. However, actively updating digitised corpora, as well as providing a specific contact form to signal problems with items in a collection could facilitate improvements. As many digitised sources are spread over the web with the same digital copy of a source in archive.org, GoogleBooks, and HathiTrust, locating the responsible institution in order to improve or complete the digital source is difficult.

Due to the existence of digital copies with missing pages or incomplete or low quality scans, knowing that different copies of the same source circulate, has different consequences depending on the version that you use. Differentiating between copies is much easier using metadata such as the year of scanning, type of scanner, software, the producing institution, and url’s, from the institution’s website or in the PDF and is slowly becoming a standard practice. Referencing digital sources in footnotes however, needs to improve. As Tim Hitchcock said “The vast majority of […] sources are now accessed online and cherry-picked for relevant content via keyword searching. Yet references to these materials are still made to a hard copy on a library shelf, […]. By persevering with a series of outdated formats, and resolutely ignoring the proximate nature of the electronic representations we actually consult, the impact of new technology has been subtly downplayed”.[3] The vast pool of digital sources on the internet can be more transparent in our footnotes if we state the website/institution where we acquired the source and integrate the source tracking number, url or doi. This is especially important when other researchers point to missing details or mistakes in research findings, which could be caused by the incomplete digital version of a source.

Conclusion

Although researchers often first turn to existing scans or scanning material themselves, traditional source criticism applied to new media remains important. The historian should contemplate the consequences of downloading material from provider X or Y, using scanner technique A, B or C, the need to (not) split the sources into different pieces, and process them with correct and up-to-date OCR software. Different layers of digitised sources such as colour, resolution, missing or blurred pages, the used hardware and software all impact the quality and results of your research project.

Footnotes

[1] Rose Holley, ‘How Good Can It Get?: Analysing and Improving OCR Accuracy in Large Scale Historic Newspaper Digitisation Programs’, D-Lib Magazine, 15: 3/4, March 2009; Maya R. Gupta, Nathaniel P. Jacobson, and Eric K. Garcia, ‘OCR binarization and image pre-processing for searching historical documents’, Pattern Recognition, 40: 2, February 2007, 389–397.

[2] Thank you to Maria Biryukov (C2DH) for showing me this difference.

[3] Tim Hitchcock, ‘Confronting the Digital’, Cultural and Social History, 10: 1, March 2013, 9–23, 12.