Some general thoughts for starting a Tool Criticism Blog

The pervasiveness of technology and digital tools poses new forms of challenges that can seldom be addressed by a single discipline alone. Through our series on tool criticism we would like to consider opportunities to leverage on the digital as an opportunity to bridge disciplines that presented little connection in the past: Humanities and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI).

Humanities are often described by non-humanists to have made little usage of tools before the advent of the so-called digital mega-trend, leading to what is increasingly described as “digital humanities”. This relies on the assumption that tools are predominantly quantitatively oriented, which is evidently controversial per se.

Indeed, qualitative analysis or mixed method approaches have been conducted within disciplines, and also by humanists with the help of digital tools for decades already. Digital tools designed specifically for and by humanists as we are familiar with them today can be found since the early 2000s.1 However, there is a neglect of making this transparent within the methods-parts of the scientific works, as is scientific best practice in other disciplines. Whereas it is clearly stated and argued for in research proposals and reports to funding agencies, digital tools and their impact on the research process and outcome are sparsely reflected in the methodological chapters of humanists’ works.

Unsurprisingly, the adoption of tools by humanities communities is a critical process in itself; new ways of acquiring, storing, analysing and presenting data in the humanities often call for the utilisation of tools that pre-existed in other fields and have not been developed with that precise usage or community of users in mind. Furthermore, in addition to being adopted by users in the humanities, tools are now also increasingly designed within the humanities, also for the general audience (e.g., tools allowing for augmented immersion into historical sites or building a collaborative research infrastructure).

The present blog post attempts to shed light on the “tool criticism” initiative within the humanities from the outside perspective specific to the field of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The aim is to illustrate how both fields share a common objective, and how the field of HCI offers a scientific methodology useful for digital humanities.

Among many aspects pertaining to tool criticism, the critical reflection about tools is the interpretation that helps best to make our point. What does it entail? In the field of HCI and its predecessors, the critical questioning of existing designs, or the challenging of assumptions used to justify design choices has always been a major concern. Just like a nail requires a specifically designed tool to render it useful (e.g. a hammer), digital tools also need to be regarded in relation to their purpose of use, the context and, above all, their given users.

This describes a paradigm shift away from a tool-centric view to a human-centric view, as known from physical ergonomics, cognitive ergonomics, and recent experience design: adapting tools and designing them in a user centric fashion, rather than having people adapt to existing tools. Beyond an intuitive understanding, this has become key to many critical applications because it reduces incidents, it avoids bad experiences, and it ensures data quality is not suffering in scientific applications.

In historiographic research this paradigm shift can be observed as well. Instead of “user-centred reflections”, we talk about ‘actor-centered approaches’ or the ‘microhistory turn’ in this frame. Digital tools have been developed constantly to support this shift for three decades, as for example annotation tools in Oral History2 or VennMaker to support graphic visualisations of social networks from an actor-centered point of view3. Pre-existing tools from social sciences as MAXQdA or NVivo4 were used to support the shift of focus towards a ‘microhistory’ that emphasised the narrative of the individual rather than a collective. Scholars had to deal with much more quantitative data while still conducting a qualitative analysis. 5

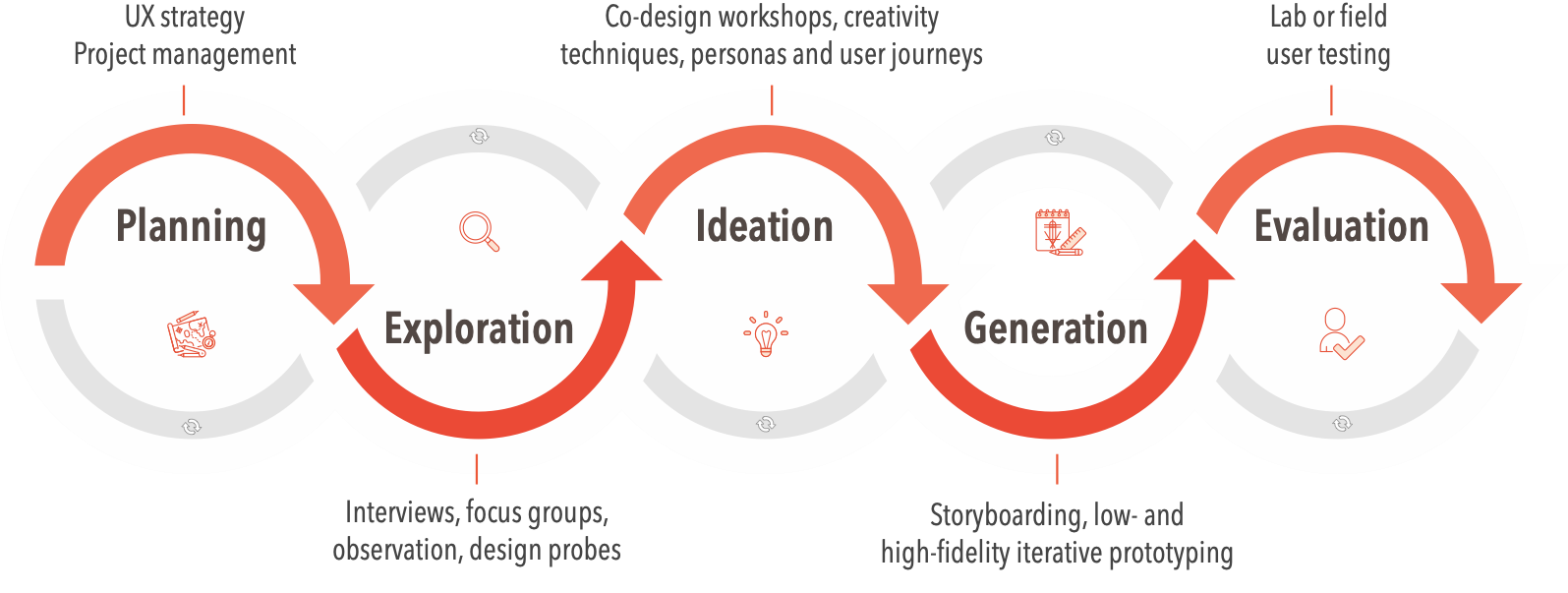

Claiming that tools should be developed with real users in the tool designers’ mind seems like an obvious statement. Still, how often is this truly the case and how many tool designs have followed established processes and methods to reach this objective? A critical reflection on a tool’s adequacy for a given set of users, their objectives and context of usage is a promising starting point and established practice in HCI. Along a structured process, tools are designed and evaluated for their successful design. At all stages, empirical data is gathered and underlies the decision taking of every design choice, avoiding misconceptions. This scientific process is iterative and implements feedback loops to verify, based on empirical user data, every single step before iterating further in the design. It allows the study of real users, independent of developers’ / tool designers’ assumptions, along five critical steps:

1. Planning

Defining the project scope, its objectives, strategy, resources, key users and stakeholders.

2. Exploration

Explore the user needs and pain points through observation, questionnaires, interviews. Revise assumptions and build a factual catalogue of needs with both qualitative and quantitative indicators.

3. Ideation

Generate a broad variety of ideas to design for the user needs, using brainstorming and synthesis methods like experience maps.

4. Generation

Translate design ideas into concrete design solutions, illustrated and tested iteratively based on sketches and prototypes of increasing fidelity and complexity.

5. Evaluation

Iterative testing of prototypes and final validation through user testing and associated methods (e.g., questionnaires, think aloud).

This process is generic and fits the design purposes of digital tools and immaterial services alike. It safeguards that eventual user experiences are as intended and can fit a variety of disciplines and fields of applications. Methods involved in the five steps are well-known or easy to understand for social scientists. Within a critical and tool-oriented approach in digital humanities, it is a good candidate for cross-disciplinary collaboration and the tackling of new challenges.

Tool criticism might not be an HCI-related topic at first glance. However, in the face of the digital megatrend, digital humanities and HCI are both concerned with preventing the technology supremacy fallacy and advocating for human-centric design. To achieve this, approved methods from HCI can easily be transferred to humanities applications for tool designs to be adequately usable and experiential. In times of growing ethical concerns with technology and also the new European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), designers have to strictly consider users’ rights and their well-being, a perspective that is central to the human-centric approach of HCI.

Notes

- RM.net – Informationsnetwerk zur Geschichte des Rhein-Maas-Raumes (DFG project 2003-2006), http://www.rmnet.uni-trier.de/cgi-bin/RMnetIndex.tcl Virtuelle Forschungsinfrastruktur FuD running since 2004, https://www.kompetenzzentrum.uni-trier.de/de/projekte/projekte/fud/; VennMaker Social Networkanalysis, http://www.vennmaker.com/ started before 2006.

- For example, the oral history tool box provided by the Oral History Association: http://oralhistorianstoolbox.cohds.ca/

- http://www.vennmaker.com/funktionen_und_anwendungen?lang=en; See also: Gamper, Markus; Schönhuth, Michael; Kronenwett, Michael (2012): Bringing Qualitative and Quantitative Data Together: Collecting Network Data with the Help of the Software Tool VennMaker. In: H. Safar (Hrsg.) Social Networking and Community Behavior Modeling: Qualitative and Quantitative Measures. Hershey (USA).

- Case studies in historical research can be read in these blogs: https://katebradleyhistorian.wordpress.com/2012/06/01/why-historians-should-love-nvivo/; https://lirecrire.hypotheses.org/540

- Levi, Giovanni: On Microhistory. In: Peter Burke (ed.): New Perspectives on Historical Writing. Cambridge 1991. p. 93-113.